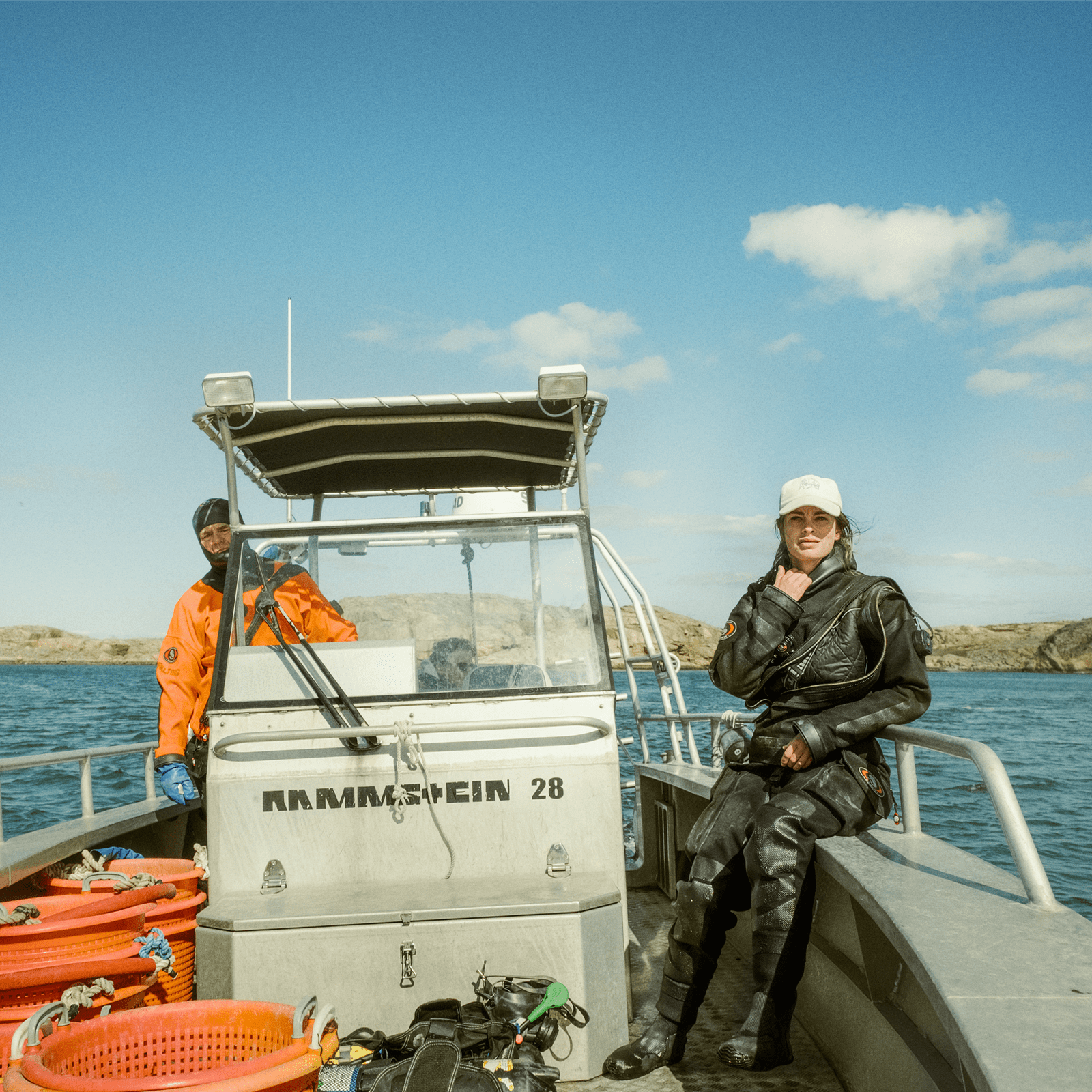

After leaving behind her career in marketing with H&M, Lotta Klemming is now one of Sweden's few female oyster divers, working for Klemmings Ostron, her family's 30-year-old seafood business on an archipelago outside Grebbestad. Lotta worked in Gothenberg for seven years, where she thought she would ‘stay and climb as far as I could and hoped that somewhere along the way I'd like my job’. ‘It was a hamster wheel and I was so ambitious. I opened new stores around the world and so I traveled a lot.’ Despite her ambition, the job didn't give her the fulfillment that she thought it would. On a trip home to visit family, Lotta went diving for oysters. ‘I've always been enamored with the sea and [I] learned to scuba dive as a kid, so I don't know why it took me so long. It wasn't until I was 26 that I went oyster diving,’ says Lotta, who'd watched her father and uncle dive for them for their business throughout her childhood.

‘I had an image that I needed to be like my father to do it and had seen it as a man's job, but I've always been connected to the sea. I was desperate to find something else in my life that I loved, and I was good at it. I hadn't had that feeling before with anything. It was my calling.’ Caring for and collecting the oysters is just one side of her job – when she's not below the water, Lotta runs educational experiences for groups who want to learn more about shellfish and connect with the sea surrounding Sweden. ‘Harvesting is the heart of the business and it's a difficult process to bring them up from the water. They grow wild on the bottom [of the seabed], and they grow together, so there's a lot of work to disconnect them when diving.’ It's a physical and exhausting job in a place where environmental elements are working against you.

Keeping a business like this profitable year on year is one of the hardest elements for Lotta. ‘We sell the oysters directly to restaurants around Sweden. We're completely transparent and want to bring back handcrafted fishing, as we've seen so much damage from industrial fishing in the North Sea. Oysters will always be seen as an exclusive and in-demand product; people know they're premium but ours are wild – that's extremely rare, and the way that we fish and dive for them is even rarer,’ she says. Maintaining traditional farming methods isn't the easiest option, but it's what keeps Lotta connected to the sea and to her family's heritage.

A version of this article was first published in Courier issue 49, September/October 2022. To purchase the issue or become a subscriber, head to our webshop.